Background:

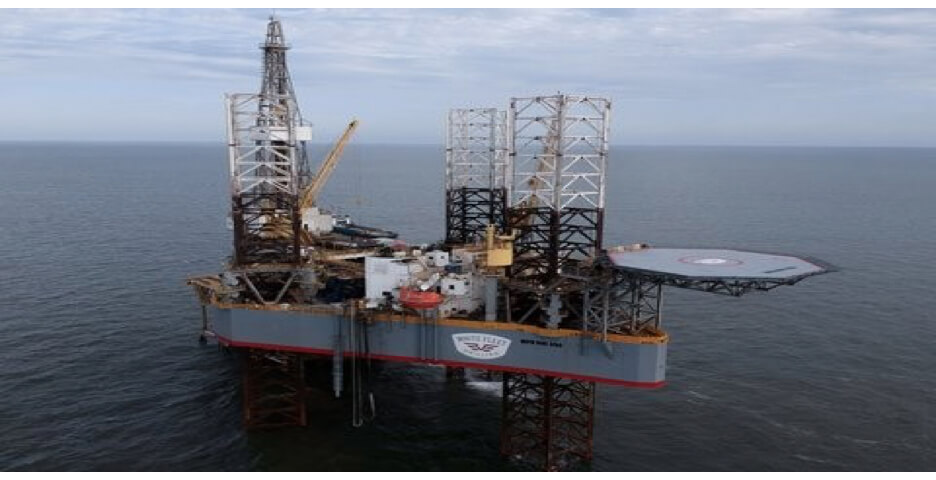

Gilbert Sanchez, an employee of Smart Fabricators of Texas, LLC, (“Smart Fab”) performed welding work on different offshore-type drilling rigs. In August 2018, while working on the ENTERPRISE 263, a jacked-up drilling rig owned and operated by Enterprise Offshore Drilling LLC, (“EOD”) Sanchez tripped on a pipe and injured his back and ankle. Sanchez sued EOD and Smart Fab in Texas state court, asserting negligence under the Jones Act and General Maritime Law claims, including unseaworthiness, and seeking medical expenses (“Cure”), lost wages, and exemplary damages.

EOD and Smart Fab removed the case from state to federal court, arguing that the federal court has subject-matter jurisdiction because Sanchez’s injury occurred while he was working on a drilling rig jacked up on the Outer Continental Shelf, thereby triggering the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (“OCSLA”), which borrows the compensation scheme of the Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act (“LHWCA”).Sanchez then dismissed his claims against EOD and moved to remand the case back to state court, arguing that he was a Jones Act seaman, not an OCS longshoreman, and that his claims under the Jones Act precluded removal of the case to federal court.

Issue presented:

The critical issue in the case is whether Sanchez was a Jones Act seaman at the time of his injury. If he was, his case should be remanded to state court. If he was not a seaman, his case was properly removed, and his remedies are limited by the LHWCA, which was adopted under the OCSLA as the compensation scheme for injured workers.

The Evidence:

Sanchez presented evidence that the drilling rigs he worked on for Smart Fab are “vessels in navigation.” He testified that his work involved “construction, maintenance, and welding” critical to the drilling rigs’ function. He testified that he had been working for Smart Fab for several months before the injury and that he spent the majority of his time working on, and was aboard the drilling rigs, where he also slept and ate his meals.

Smart Fab argues that, of the 67 days Sanchez had worked for the company before he was injured, two days were spent in a shop on land; 48 days were working on the ENTERPRISE WFD 350 (a jacked-up drilling rig located next to a dockside pier); and 13 days were on the ENTERPRISE 263 (a jacked-up drilling rig resting on the seafloor on the Outer Continental Shelf). Smart Fab contends that when Sanchez was working on both the Enterprise drilling rigs, they were undergoing extensive repairs and were not operating or navigating. Finally, according to Smart Fab, while Sanchez spent over 70% of his time aboard the two Enterprise jacked-up drilling rigs, he was doing work that did not expose him to the “perils of the sea”, such that he cannot be considered a member of a vessel’s crew or Jones Act seaman. (Id.).

The Enterprise 263’s operator testified that Sanchez’s work was limited to welding and fitting different equipment on the jacked-up drilling rigs, and that he did not operate or navigate the rig.

What is required to be a Jones Act seaman:

Although the Jones Act does not define “seaman,” Congress has elsewhere defined it as the “master or member of a crew of any vessel.” 33 U.S.C. § 902(3)(G) Since that time, a two-prong test has developed to determine whether an employee is a Jones Act “seaman:

1) The employee’s duties “must contribute to the function of the vessel or to the accomplishment of its mission”; and

2) The employee “must have a connection to a vessel in navigation (or to an identifiable fleet of such vessels) that is substantial in terms of both duration and nature.”

Smart Fabricators concedes that Sanchez’s “work as a welder on the Enterprise 263 may have contributed to its function,” satisfying the first prong.

However, the parties dispute the second prong, whether Sanchez worked on a “vessel in navigation” and, if he did, whether his connection to the “vessel” was “substantial in terms of both duration and nature.” (Note that the Fifth Circuit generally has declined to find seaman status when a plaintiff spends less than 30% of his or her time aboard vessels in navigation.)

Whether a plaintiff is a seaman depends “not on the place where the injury is inflicted … but on the nature of the seaman’s service, his status as a member of the vessel, and his relationship … to the vessel and its operation in navigable waters”. “The fundamental purpose of this substantial connection requirement is to give full effect to the remedial scheme created by Congress and to separate the sea-based maritime employees, who are entitled to Jones Act protection, from those land-based workers, who have only a transitory or sporadic connection to a vessel in navigation, and therefore whose employment does not regularly expose them to the perils of the sea.”

Sanchez is a “seaman” if his “work regularly exposes [him] to ‘the special hazards and disadvantages to which [seamen] who go down to sea in ships are subjected.” “Land-based maritime workers do not become seamen because they happen to be working on board a vessel when they are injured, and seamen do not lose Jones Act protection when the course of their service to a vessel takes them ashore.”

A: “Vessels in Navigation”:

The parties first dispute whether the two jacked-up drilling rigs on which Sanchez worked were “vessels in navigation” at all. However, in Stewart v. Dutra Const. Co. , 543 U.S. 481, 125 S.Ct. 1118, 160 L.Ed.2d 932 (2005), the Supreme Court clarified the definitions of “vessel” under the LHWCA and “vessel in navigation” under the Jones Act. Part of the test for determining whether a watercraft is a “vessel” is whether the craft is “used, or capable of being used” for maritime transportation. If a watercraft is “a vessel” under § 3 of the LHWCA, it also is a “vessel in navigation” under the Jones Act. With respect to the requirement that a vessel be “in navigation,” the Supreme Court clarified that the requirement was meant to show only that structures could lose their vessel status if they are withdrawn from the water for extended periods. (The Supreme Court eschewed a separate “in navigation” requirement; the “in navigation” element is subsumed into the definition of “vessel”).

Moreover, recent Fifth Circuit cases hold that “jack-up drilling platforms … are considered vessels under maritime law.” (a drilling rig that was in a jacked-up position during the incident was a vessel.) The record does not show that the Enterprise drilling rigs were incapable of being used for maritime transportation.

Smart Fab then argued that “[t]he rigs were not operating or navigating when [Sanchez] was aboard them, but rather were undergoing extensive repairs.” In Chandris, 515 U.S. 347, 115 S.Ct. 2172, the Supreme Court stated that “[t]he general rule among the Court of Appeals is that vessels undergoing repairs or spending a relatively short period of time in drydock are still considered to be ‘in navigation,’ whereas ships being transformed through ‘major’ overhauls or renovations are not.” Chandris, 515 U.S. at 374, 115 S.Ct. 2172. The Court suggested that a 6-month drydock repair is insufficient to take a vessel out of navigation, but a 17-month project is likely enough. Smart Fab did not submit any evidence showing when the ENTERPRISE 263 and the ENTERPRISE WFD 350 were undergoing repairs; how long any repairs took; whether the repairs were a major overhaul or not; or whether the rigs had become “[in]capable of being used for maritime transportation.” The District Court found that Smart Fab had not shown that the ENTERPRISE 263 and ENTERPRISE WFD 350 were no longer vessels in navigation due to extensive repairs

B. Sanchez’s Connection with the Vessels:

Smart Fab submitted evidence that Sanchez began working for the company on August 17, 2017 and had worked a total of 67 days when his injury occurred. Because Sanchez spent more than 30% of his time working aboard the two drilling rigs, he satisfies the minimum-duration requirement.

The District Court concluded that Sanchez’s connection to the vessels was “not substantial in nature”. The District Court focused its inquiry into the nature of the employee’s connection to the vessel and whether the employee’s duties take him to sea. The District Court determined that its review of Sanchez’s work and working circumstances shows that he did not have the necessary connection to the two drilling rigs.

Sanchez did not submit evidence showing that he was assigned to either vessel as a “crew member”. The rig manager for the Enterprise 263 testified that Sanchez was not a crew member and could not operate the rig. (Docket Entry No. 14-2 at ¶ 10). The fact that Sanchez sometimes ate and slept aboard, and did welding work on the rigs, did not make him a crew member of either rig, according to the District Court

The District Court also concluded that Sanchez failed to show that the duties he performed for Smart Fab on the two drilling rigs exposed him “to the perils of the sea”. The District Court viewed the facts in Sanchez to be distinguishable from those in Naquin v. Elevating Boats, LLC , 744 F.3d 927 (5th Cir. 2014), in which the plaintiff ordinarily worked aboard lift-boats while they were moored, jacked up, or docked in the defendant’s shipyard canal. Naquin spent approximately 70% of his time working aboard the lift-boats, “inspecting them for repairs, cleaning them, painting them, replacing defective or damaged parts, … and operating the vessel’s marine cranes and jack-up legs.” The district court found that the plaintiff in Naquin was not a seaman because he worked only on lift-boats that were moored, jacked up, or docked. However, in Naquin the Fifth Circuit reversed, holding that the plaintiff’s primary duties were performing the “ship’s work on vessels docked or at anchor in navigable water,” and that “[i]n doing this work, [the plaintiff] faced precisely the same type and degree of maritime perils faced by” a seaman at sea. The Fifth Circuit also cited In re Endeavor Marine Inc. , 234 F.3d 287, 292 (5th Cir. 2000), where a worker whose primary responsibility was to operate the cranes on board a vessel to load and unload cargo had the substantial connection to the vessel needed to qualify as a seaman.

The District Court concluded that, unlike the plaintiff in Naquin, whose job duties included operating the lift-boats’ marine cranes and jacked-up legs, Sanchez’s duties did not include, and he was not involved in, tasks requiring operating or navigating the rigs, such as “line-handling, steering, watch-standing, engine operation, or any drilling-related function.” The Court noted that Sanchez was injured when he tripped on a pipe welded to the drilling-rig deck, and that such an injury was of a type, and from a risk, that longshoremen commonly face in their work, and not from the perils a seaman faces at sea.

The District Court concluded that the record evidence does not show that the circumstances or the nature of Sanchez’s duties exposed him to the perils of the sea in a manner associated with seaman status. The Court found that Sanchez had not alleged facts or submitted evidence showing that he had a substantial connection with a vessel in navigation as a seaman. Consequently, the District Court found that Jones Act does not apply, the LHWCA does, and the case was properly removable to Federal Court.

The case on appeal (decision issued Aug 14, 2020):

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit found that, based on established case law, Sanchez does qualify as a Jones Act seaman, so that the case should be remanded from the Federal District Court to the Texas State Court.

The Fifth Circuit noted that Sanchez performed a total of 91% of his work aboard the two drilling rigs (72% on the ENTERPRISE 350 and 19% on the ENTERPRISE 263), so there was no concern about the “at least 30%” requirement. But as Sanchez’ injury occurred on the 263, the Court looked to see if Sanchez’ work aboard that rig was “substantial in terms of both duration and nature”. The parties agree that Sanchez meets the first prong of the test, as he was “doing the ship’s work” in contributing to its function or mission. The dispute remains as to the second prong of the test, whether he has a sufficient relation to the navigation of the vessels and the perils attendant thereto. The Court examined the duration of the work aboard, and of course had no difficulty concluding that the duration was sufficient.

The difficulty arose with the “quality (nature) of the worker’s duties aboard a vessel”, focusing on the nature of the claimant’s connection with the vessel. “For the substantial connection requirement to serve its purpose, the inquiry into the nature of the employee’s connection to the vessel must concentrate on whether the employee’s duties take him to sea” or are for “those workers who face regular exposure to the perils of the sea”.

The Fifth Circuit, in overturning the District Court, noted that prior caselaw rejects such a narrow reading of the substantial-in-nature requirement. The Court noted in another case that seaman status was met by an employee’s work was substantial in nature, even though he worked from a dock loading and unloading vessels, helped maintain the crane, but rarely stepped aboard a moving vessel. His exposure to “the hazards of the sea” were met because he worked on the brown water of the Mississippi River.

Recalling Naquin, the Court reiterated that “working on a vessel docked or at anchor in navigable waters satisfied the substantial in nature requirement”. Because the relevant facts in Naguin are indistinguishable from those in Sanchez, the Fifth Circuit reverses, and remands.

Note however that Circuit Court Judge Eugene Davis issues a concurrence which reads like a dissent; he believes the Fifth Circuit precedent discussed above is out of harmony with US Supreme Court opinions, and asks that the entire Fifth Circuit, sitting en banc, come together and reconsider this decision.

So, stay tuned?

If you would like more information about the above article, or other matters related to injuries to seamen, please contact us at the Herd Law Firm, PLLC.