The COVID-19 pandemic still rages unabated in April 2020, impacting lives, businesses, individuals and industries, in ways that will change the world forever. The International Labor Organization (“ILO”) predicts that as many as 25 million jobs worldwide could be wiped out by a worldwide recession brought about by the pandemic. Many governments around the world have imposed a “lockdown” to restrict the movements of its citizens and to control the rapid and virulent spread of the pandemic. In Southeast Asia, the lockdown was implemented in several stages throughout the region.

On March 15th, the Indonesian government formed the National Disaster Management Agency (“BPNP”) and declared a National Disaster- Non-Natural situation until May 29th. It has requested all citizens to work, study and pray from home. The Malaysian government also announced a national lockdown on March 18th, which recently was extended to April 14th. Specific exceptions have been given to transportation and some other essential service sectors.

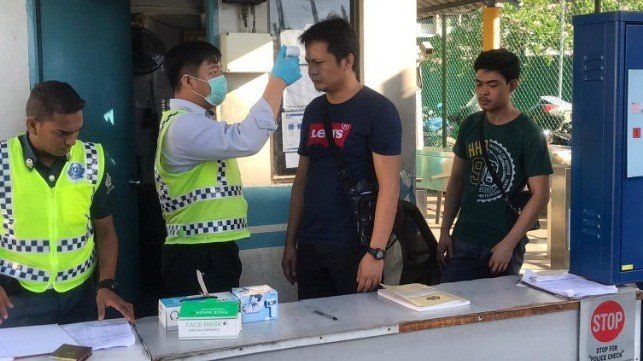

Singapore announced “circuit breaking” measures on April 3rd, a euphemism for lockdown. The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore has implemented temperature screenings at all sea checkpoints. Other precautionary measures have been taken as well, such as: prohibiting shore-leave for personnel in Chinese ports, mandatory temperature checks, keeping a log of crew movements, and restricting staff travel to China.

Thailand announced a state of emergency on March 26th, with lockdown measures in effect until April 30th. The borders are closed to all foreign visitors; domestic travel is heavily restricted, with all but essential businesses closed until the lockdown expires. A 24-hour curfew was implemented on April 3rd, with all but essential activities prohibited.

In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte has extended the original lockdown until April 30th, since declaring a state of emergency on March 25th. Commercial aviation and shipping are banned, and land transportation operates under heavy restrictions.

The predicament of the passengers and crew aboard cruise ships and the cruise industry as a whole also has come into the limelight. Cruise ships, with large numbers of passengers and crew and an emphasis on communal dining and group activities, became incubators of the COVID-19 virus, and infections on ships like the Diamond Princess have been described by passengers as “floating nightmares”.

The predicament of the passengers and crew aboard cruise ships and the cruise industry as a whole also has come into the limelight. Cruise ships, with large numbers of passengers and crew and an emphasis on communal dining and group activities, became incubators of the COVID-19 virus, and infections on ships like the Diamond Princess have been described by passengers as “floating nightmares”.

Beginning March 15, Australia banned cruise ships arriving from foreign ports, with a few exemptions for ships already en route. Many countries in Southeast Asia also banned cruise ships from disembarking their passengers, for fear of importing the virus through infected passengers and crew. Cruise ships such as the MS Zaandam and Rotterdam, both operated by Holland America Line, were denied entry at ports throughout Central and South America as well. Globally, concerns over COVID-19 cause great difficulty in finding ports willing to receive cruise ships and allow them to disembark passengers. Overall, these incidents have posed the question of whether the cruise industry was even remotely ready for the virus and how well they will recover from the effects of this pandemic.

Many countries have responded to the pandemic by imposing lockdown or restricting movement. Some retailers and manufacturers failed to pick up their cargo and containers because their warehouses are full or closed. Some ports remained open, but have reduced workforce, which exacerbates cargo congestion. Cargo congestion in turn causes disruption of the supply chain, including movement of essential goods and foodstuffs. Cargo lying uncollected at ports creates congestion and takes up space, reducing capacity for incoming cargo and containers.

Some ports have taken the precaution to declare ‘force majeure’, to pre-empt claims and legal liability. The closure of ports and port congestion have caused disruptions in the supply chain and import and exports.

The pandemic also exposes the fragility of the global supply chain and has brought into acute focus the shortages of critical medical components needed in the fight against the pandemic. Wuhan Province in particluar and China in general were important manufacturing bases for manufacturing of key components for companies like Apple. The pandemic lockdown and responsive measures taken stopped manufacturing of crucial component items and disruption of supply chains.

Countries ravaged by the pandemic find it hard to provide adequate medical care, due to shortages of critical medical equipment such as ventilators, protective masks and other gear. In the U.S., the shortage has multiple causes, including problems with the global supply chain. Before the pandemic, for instance, China produced approximately half the world’s face masks. As the infection spread across China, their exports came to a halt. Now, as the infection spreads globally and transmission in China slows, China is shipping masks to other countries, but the United States has not been a major recipient.

Among aviation and maritime workforce, the Philippines, China, India and Indonesia are among the biggest suppliers of crew members. Airline and port restrictions in most of these countries have made it nearly impossible for crew members to get home without special government arrangements. The safe repatriation of the crew from the vessels will require the joint efforts of the governmental agencies, the crew manning agency and the owners.

The disruption of shipping and logistics due to the pandemic has an impact on insurance as well. Cargo owners, importers, risk managers and insurers need to monitor closely the implications of the disruption, which include reduced cargo and stock throughput, delays, and additional costs associated with rerouted and perishable goods.

The disruption caused by the pandemic has legal effects as well. The cargo owner who charters vessels to ports to load or to discharge cargo is required to nominate a “safe port”, or a port where the vessel can safely call, conduct its cargo operations, and then safely leave. When the intended port is closed, the cargo owner or charterer would be obliged to nominate an alternative port, but now this may not be possible, as there may not be an alternative destination where the cargo can be discharged.

If the cargo is non-essential cargo, it cannot be moved to the ports during a national lockdown. This may result in the vessel arriving at the port and finding no cargo to be shipped, causing demurrage to be charged, an often-costly fee payable for failure to load or discharge ship within the time agreed.

Also, before the vessel can take on cargo, it must be cleared by the health authorities of the port, a process known as obtaining “free pratique.” In the pandemic-affected countries, the process of vetting the crew may take time, and the legal responsibility for this delay likely will fall on the shipowner, rather than on the charterer.

The effects of the pandemic may possibly be covered in the “force majeure” clauses in some contracts, which is a provision which excuses one or both parties’ performance obligations when circumstances arise which are beyond the parties’ control and make performance of the contract impractical or impossible. However, these clauses are not uniform in contract law and may not apply or be available.

While each of these legal issues and disputes may not arise immediately, they surely will surface under certain circumstances and may determine who will bear or share the financial losses, once countries recover from the immediate effects of the pandemic.

The above is a summary of one or more news stories reviewed by the author of this article. It may contain comments or views of the author only.

This article is intended for general interest and does not constitute legal advice.